Cellular regenesis

Redesigning cells beyond evolution’s limits

What might the humans of tomorrow look like?

Science fiction often gravitates toward two radically different visions of the future. In the world of Gattaca, genetic destinies are meticulously edited from the moment of conception, promising lives free from disease and minds optimized for achievement. In The Six Million Dollar Man, biology is surpassed by machinery: flesh and bone yield to metal and circuits, creating limbs stronger and organs sturdier than evolution alone could produce. Both of these vaguely unsettling futures are closer than most realize, with companies already offering embryo screening for traits like intelligence and artificial hearts for end-stage heart failure.

But counterintuitively, the most human future may lie somewhere in between: replacing every cell in our bodies with enhanced versions, designed to be more efficient, resilient, and capable than those we've inherited from evolution. In this essay, we'll explore how this cellular revolution is already underway, consider how replacing cells throughout the body could extend lifespan, and imagine even more radical ways to reshape our biology while preserving what makes us fundamentally human.

In some ways, this future resembles another sci-fi trope: nanobots invisibly swarming through bodies, constantly monitoring health and repairing damage. This idea is often associated with K. Eric Drexler’s Engines of Creation, a book now remembered largely for its provocative warning about self-replicating “grey goo.” But unlike Drexler’s artificial and potentially dangerous nanobots, our friendly little helpers will simply be upgraded versions of the extraordinary living nanomachines we're already made of.

Of course, these ideas may provoke unease. Who are we to rewrite biology itself? Yet humans have always pushed against the boundaries set by nature. Every antibiotic prescription, every cancer treatment, every heart bypass surgery is already a rebellion against the biological hand we've been dealt. If we intervene readily once illness strikes, isn’t it logical, and perhaps even morally imperative, to explore ways to prevent diseases entirely?

This essay, then, is an invitation to imagine audacious futures, confront their ethical complexities, and reflect upon what it means to remain human.

A precarious civilization

The year is 2025. Scientists have just discovered an untouched alien civilization. Trillions of individuals, each carrying an identical genetic blueprint, operate in perfect synchrony as a single, unified collective. Yet within this hive, something astonishing occurs: each individual develops its own distinct personality and specialized role—relaying critical information, fending off threats, or diligently maintaining infrastructure.

We embark on a mission to study this civilization from afar, carefully observing but never interfering. For decades, their ecosystem appears balanced, swiftly correcting minor disturbances. But slowly, cracks begin to form. The guardians become lethargic from the constant burden of fighting invaders. A rogue individual establishes a destructive cult that quietly spreads like wildfire. Gradually, what was once a thriving utopia slides toward collapse.

Yet this alien civilization isn't on some distant planet—it exists within each of our bodies.

The selfish genome

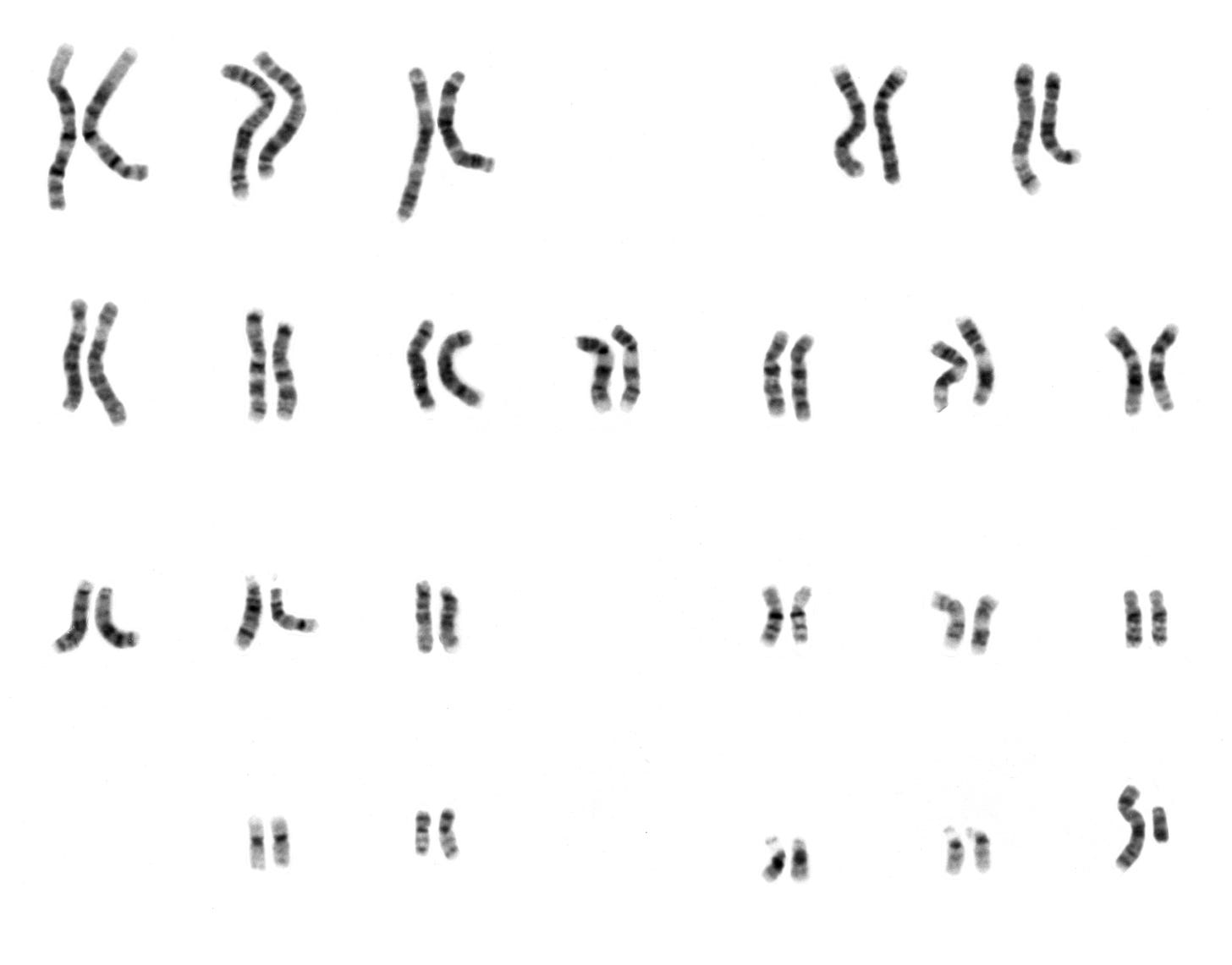

We all begin life as a single cell. From the moment sperm meets egg, a precise developmental choreography unfolds: cells divide, specialize, and organize into tissues and organs, ultimately creating a body composed of trillions of specialized cells. Neurons transmit electrical signals, T cells defend against pathogens, and fibroblasts maintain tissue integrity. Despite their differences, these cells all originate from the same genome.

In Cellular Alchemy, I explored how a single genome generates such remarkable diversity. The key lies in epigenomics, the genome’s ability to sense environmental cues in order to activate specific genes at precise times and places. This selective activation in different cell types guides the body along its developmental journey, from embryo to adult. But this versatility also brings inherent tradeoffs: because the genome must retain instructions for every possible cell type, it can't be perfectly optimized for any single role.

Such evolutionary compromises run deep within our biology. Developmental genes, critical for building the body, can trigger cancer if mistakenly reactivated later in life. Similarly, our immune systems evolved to aggressively protect us against pathogens during vulnerable early years. While this heightened vigilance is essential for early survival, it frequently backfires, overreacting to harmless triggers and causing autoimmune diseases and chronic inflammation. Ultimately, evolution shaped our genome to build organisms optimized for reproduction, not for the long-term performance of individual cells.

But what if we could redesign every cell type individually, freeing each from evolution’s compromises? It might sound like science fiction, but as we'll soon see, this revolution is already underway.

The superhumans among us

Sickle cell disease is a perfect example of how evolution optimizes for passing on genes rather than for the long-term health of individuals. People born with two copies of a specific genetic mutation produce red blood cells shaped like crescent moons, prone to painfully clogging vessels. Yet those who inherit only one copy of this mutation are protected against malaria, a significant survival advantage in regions where this disease is still common. Evolution preserves this mutation because it benefits the population as a whole, despite devastating consequences for those individuals who inherit two copies. But this doesn't mean we should accept the suffering it causes, especially if we have strategies to intervene at the cellular level.

Even with powerful gene editing tools like CRISPR at our disposal, treating genetic diseases is rarely straightforward. Researchers must first pinpoint exactly which cells are affected by a harmful mutation, then edit enough of them to significantly improve patient health, a challenging feat with current methods. Fortunately, sickle cell disease presents an unusually favorable scenario. The disease clearly impacts red blood cells, which originate from versatile blood stem cells. These stem cells can be safely extracted from patients, carefully modified in the lab, and returned to the body where they steadily multiply, providing a continuous, lifelong supply of healthy blood cells.

In 2020, Victoria Gray became the first person to receive this treatment, now known as Casgevy. Today, she is effectively cured and serves as an inspiring advocate for genetic medicine, a testament to how editing just a single cell type can profoundly change a life. Yet Casgevy merely restores an ability most of us take for granted—what if we could cure even more diseases by giving our cells entirely new capabilities?

The immune system is our biological frenemy: fiercely protective, but prone to dangerous overreactions. Evolution favors aggressive defenses for survival, preferring false alarms over missed threats, even though this often leads to autoimmune disorders and inflammation. Yet cancer presents a unique challenge. Because tumors arise from our own cells, they often slip past the immune system undetected. Early cancer therapies tried to use drugs to broadly activate immune responses but ran into the same fundamental paradox: they successfully shrank tumors, but frequently triggered severe autoimmune reactions.

What if we could transform the immune system from a sledgehammer into a scalpel, precisely cutting away disease while sparing healthy tissues? CAR-T therapy achieves exactly this by genetically modifying T cells, the immune system’s frontline defenders, to express synthetic "chimeric antigen receptors" (CARs). These receptors don’t exist naturally; scientists design them from scratch, cleverly repurposing cells’ inherent sensing abilities to precisely target cancer. Armed with CARs, engineered T cells recognize and precisely eliminate tumors while leaving the rest of the body unharmed.

The idea of genetically engineering our own cells might seem unsettling in the abstract, but that discomfort quickly dissolves when we witness the lives these therapies have saved. In 2012, Emily Whitehead was six years old, fighting leukemia that chemotherapy could no longer stop. With few options left, she became the very first person to receive CAR-T therapy, her own immune cells reprogrammed and sent back into battle against her cancer. Today, not only is Emily alive, she’s healthy and attending college. Thousands more have been given a new chance at life thanks to similarly engineered cells, yet from the outside you'd never even know they carry this extraordinary technology within them.

Yet despite their transformative power, these therapies fix only one cell type at a time, leaving us trapped in a perpetual game of biological whack-a-mole as new problems inevitably emerge elsewhere.

Macro vs. micro replacement

Therapies like Casgevy and CAR-T demonstrate that we can repair or even enhance individual cell types. Yet the human body comprises trillions of specialized cells, with each role uniquely vulnerable to damage and decline. Even if engineered T cells could flawlessly eliminate every cancer, they wouldn't prevent the quiet deterioration of heart muscle cells that gradually leads to heart disease. Addressing cell types one by one will never fully halt the broader, systemic decline we call aging.

Aging researchers often compare the human body to a car: both depend on interconnected parts, and the failure of even one component can compromise the whole. Yet a car can run smoothly for decades if worn-out parts are proactively replaced before they fail. What if we could do something similar for the human body, addressing vulnerabilities before problems emerge?

Proponents of this strategy, known as replacement, envision a future in which preventative organ transplants become as routine as oil changes. Yet translating this vision into reality quickly runs into practical challenges.

First, there’s the question of where all these replacement organs would come from—we already face severe shortages today. Optimists highlight artificial organs, lab-grown tissues, animal-to-human xenotransplants, and improved preservation methods. Yet these techniques remain largely experimental, reserved for extraordinary circumstances when all else has failed, and each faces substantial medical hurdles and practical obstacles to widespread adoption.

Even if these supply issues were resolved, transplant surgery itself remains inherently risky. With current techniques, few surgeons would willingly perform a heart transplant on an otherwise healthy 40-year-old, regardless of how ideal the replacement organ might be. And even if future AI-driven robotics dramatically improve surgical precision and reliability, the challenge of vascularization, the delicate process of connecting new tissue to the body's intricate network of blood vessels, remains daunting.

Moreover, each organ presents its own unique biological puzzle, multiplying these already formidable challenges many times over. And even if we overcame every obstacle mentioned so far, one profound barrier would remain: the brain. You can’t simply replace your brain without losing the memories, identity, and consciousness that define who you are.

In Replacing Aging, neuroscientist Jean Hébert proposes an imaginative solution to the unique challenge posed by the brain. Since full replacement would sacrifice identity, he suggests a gradual approach: first quieting older brain regions, then carefully introducing young, healthy cells to take over their functions. Though this concept might seem radical, evidence from glioma surgeries suggests it could be feasible. Patients undergoing these procedures often retain critical functions like language, even after surgeons remove regions traditionally considered essential, highlighting the brain’s extraordinary ability to reorganize itself.

Admittedly, numerous technical hurdles remain before most of us would willingly volunteer for Hébert’s brain replacement approach. Still, it feels more intuitively plausible than fantasies of uploading our minds. In the nearer term, if a gradual, cell-by-cell strategy might feasibly work in an organ as intricate as the brain, why not apply it throughout the rest of the body? After all, biology’s fundamental unit is the cell; it makes sense to direct our interventions precisely at that scale. Joe Betts-LaCroix at Retro Biosciences calls this concept "micro-replacement." Pursuing micro-replacement would not only yield more immediate successes but also offer critical insights as we build toward the eventual goal of addressing the brain itself.

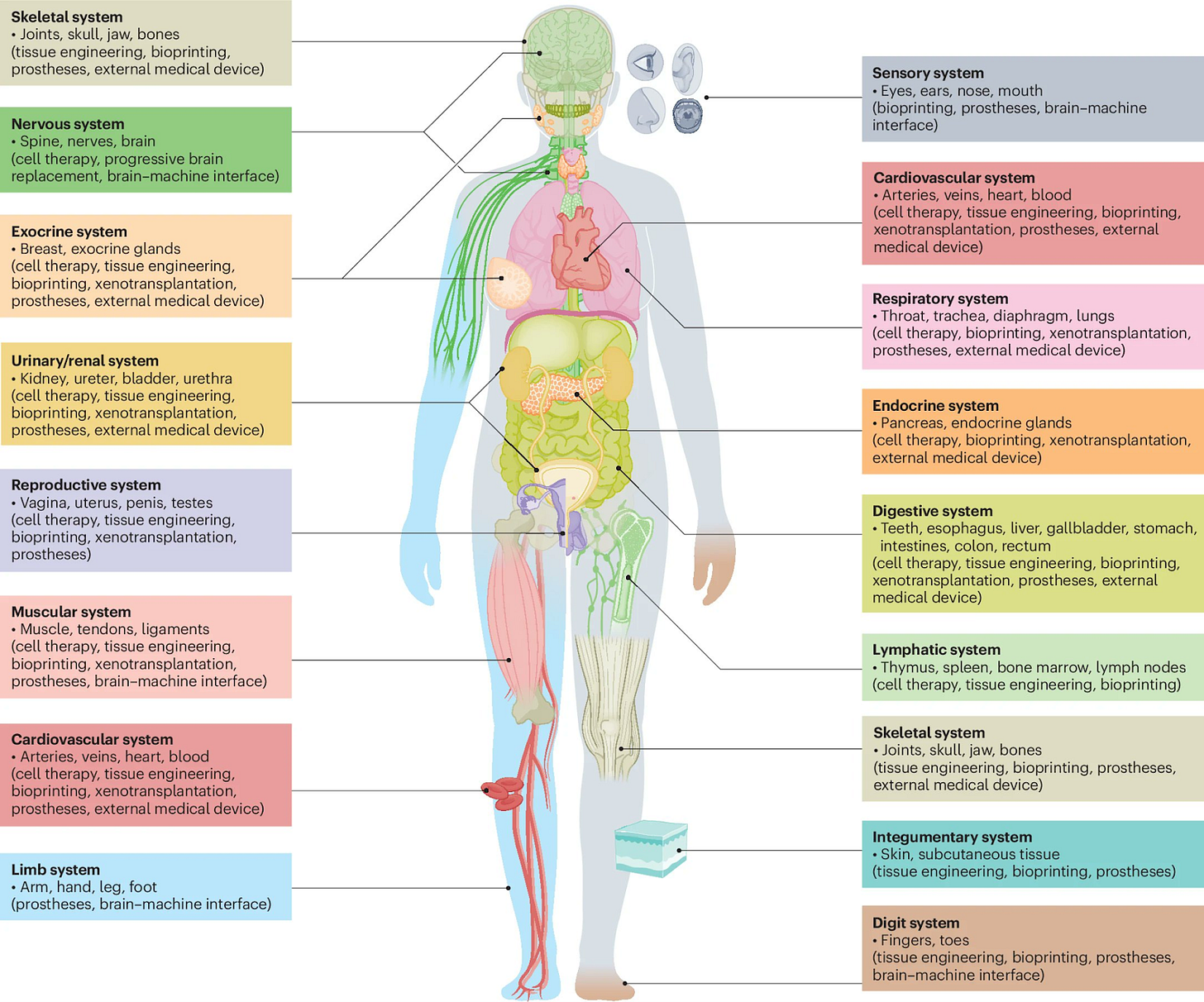

In my previous essay, Cellular alchemy, I discuss why the cell is the natural unit for replacement and explore the technologies required to create every cell type in the body. Here, I'll just briefly summarize some of the main reasons:

First, therapies like Casgevy and CAR-T demonstrate that we can already safely deliver replacement cells into the body, particularly for certain accessible cell types, such as those in the blood. While immune compatibility and production challenges remain significant obstacles, innovations such as universal donor cells and autonomous cell manufacturing could help overcome them. In other cell types, effective delivery remains an ongoing challenge, likely requiring continued improvements in gene therapy approaches such as engineered viral vectors or lipid nanoparticles.

Second, replacing individual cell types involves fewer variables than engineering whole organs. Rather than replicating the complex mixture of nutrients, growth signals, and mechanical forces required to grow entire tissues in bioreactors, we can precisely control cell identity by activating or silencing specific sets of genes. This approach becomes simpler still when working with progenitor stem cells, which naturally multiply and differentiate into specialized cell types. Leveraging both cellular programmability and innate developmental potential significantly reduces the number of strategies and cell types we must optimize.

Finally, cellular rejuvenation through epigenetic reprogramming is perhaps the most crucial aspect of micro-replacement. This process acts almost like biological alchemy, resetting a cell’s internal age, erasing accumulated damage, and enabling rejuvenated cells to revitalize existing tissues. By carefully adding the right combination of factors, we can coax aged cells into rediscovering their youthful functions, restoring vitality and health at a fundamental cellular level.

But why stop at replacing aging cells with young, healthy ones that will eventually degrade themselves? What if instead we redesigned cells from the outset to be fundamentally more efficient, resilient, and capable than their natural counterparts?

First steps

What might a concrete path toward this future look like? It would likely begin modestly, with carefully targeted edits serving as proofs-of-concept to demonstrate feasibility and safety. Two therapies we’ve already discussed, Casgevy and CAR-T, offer blueprints for these first steps.

A closer look at Casgevy provides an important clue: its CRISPR approach doesn’t directly target the mutation causing sickle cell disease. Instead, it modifies a regulatory DNA region known as an enhancer, a genomic switch that controls gene activity. Specifically, Casgevy disrupts an enhancer controlling the BCL11a gene, which normally suppresses fetal hemoglobin production after infancy. By lowering BCL11a levels, the edit reactivates fetal hemoglobin, alleviating symptoms of sickle cell disease.

The broader lesson is that our genomes harbor far more therapeutic targets than we've typically considered. Historically, gene editing has focused narrowly on mutations within genes themselves, like the one causing sickle cell disease. Yet genome-wide association studies consistently find that most disease-associated mutations reside outside genes, in regulatory elements like enhancers. Even these approaches, however, greatly underestimate the possibilities, because they only reveal mutations that are universally tolerated across all cell types. By confining genetic edits to specific cell types, we can safely make beneficial changes in gene expression without causing unintended effects elsewhere in the body, dramatically expanding the number of therapeutic targets.

Earlier, we discussed how CAR-T therapy trains T cells to identify and eliminate cancer cells. Beneath that remarkable achievement lies a deeper idea: we can engineer cells to sense and respond precisely to their surroundings. Cells communicate through specialized proteins on their surface called receptors, which detect signals, also known as ligands, from the environment and trigger specific internal responses. Evolution has already fine-tuned countless receptor-ligand pairs, each dedicated to tasks ranging from nerve impulses to immune reactions. But what if we could create entirely new signaling systems from scratch, enabling cells to perform behaviors evolution never imagined?

Synthetic biology now makes this possible. Researchers have begun designing custom receptors that detect chosen signals, allowing cells to respond in precisely tailored ways. Rather than relying on evolution’s one-size-fits-all approach, these engineered receptors will allow us to activate highly specific cellular behaviors exactly where and when they're needed, minimizing unintended consequences. Researchers are now working to extend these successes beyond cancer, exploring how engineered receptors could repair damaged heart tissue after heart attacks or selectively clear harmful, senescent cells that accumulate as we age.

Together, cell-specific genetic edits and rationally designed receptors represent two complementary paths toward near-term advances in cell design. Yet as transformative as these approaches are, they still represent relatively modest adjustments. To unlock biology’s full potential, we might aim even higher: completely redesigning each cell type from first principles.

Enhanced cell replacement

Precision genome editing and rational protein design offer powerful near-term strategies, but these approaches merely refine what evolution already provides. To radically transform human biology, we could redesign each cell type from first principles. This would involve three key strategies: eliminating vulnerabilities, building resilience, and augmentation.

First, eliminating vulnerabilities means finding and removing risky genetic liabilities hidden in our cells. All mature cells carry genes they needed only during early development, but later in life these genes can accidentally switch back on, triggering diseases like cancer. Our genomes also contain remnants of ancient viruses, genetic fossils that make up roughly 8% of our DNA and may quietly contribute to aging. Yet these risks vary considerably between cell types: a gene critical to neuron function might be entirely unnecessary and thus safely removable in a muscle cell. To fully eliminate vulnerabilities, we might ask: what is the minimal set of genes required to build a heart cell that's fully functional yet adaptable? By trimming away extraneous genetic baggage, we streamline our cells and close the genetic back doors diseases use to sneak in.

Next, building resilience involves reinforcing essential cellular functions, allowing cells to maintain stable internal conditions even in the face of prolonged stresses and environmental challenges. Nature offers inspiration: muscle cells contain multiple nuclei that cooperate to sustain function, and elephants, renowned for their cancer resistance, carry extra copies of the tumor-suppressor gene p53. But true resilience goes beyond mere redundancy. Cells need sophisticated feedback systems that sense damaged genes or detect harmful changes in gene expression before they cause problems. To engineer these robust systems, we might adopt ideas from chaos engineering, deliberately introducing controlled disruptions to reveal hidden vulnerabilities. Where intuitive methods fall short, generative models could help us capture and manage the intricate, nonlinear logic of biological systems.

Finally, augmentation will equip cells with entirely new synthetic capabilities to adapt to a changing world. We could engineer cells to continuously report their status, perhaps by releasing vesicles into the bloodstream as real-time readouts of their functional state. Cells might incorporate built-in mechanisms to readily repair themselves or safely self-destruct if they become dysfunctional. Additionally, modular genomic "landing pads" could serve as predictable insertion points for new synthetic functions as they emerge. Together, these innovations would propel replacement beyond merely preserving health, allowing our cells to rapidly adopt powerful new abilities—think regenerating limbs, resisting radiation, or even photosynthesis—and fundamentally redefine what it means to be healthy.

The humans of tomorrow

While audacious, enhanced cell replacement ultimately feels truer to our humanity than other speculative visions of the future.

Compared to the Six Million Dollar Man future of artificial limbs and organs, enhanced cells are less likely to turn us into cold, unfeeling machines. Replacing ourselves with mechanical parts may lead to a pervasive, phantom limb-like disorientation, leaving us feeling disconnected from our own bodies. In contrast, carefully redesigning ourselves cell by cell will mitigate the risk of losing subtle biological functions we don't yet fully understand, such as proprioception or our delicate relationship with the microbiome.

Of course, any replacement approach raises the infamous Ship of Theseus conundrum—if you progressively replace every cell in your body, do you remain truly yourself? Yet our bodies already embody this paradox, continuously cycling through billions of cells daily. Skin renews itself monthly, blood cells are replaced every few months, and even stable neurons continuously remodel their connections. Unless you believe you become a new person with every cell division, it seems clear that continuity of self does not depend on indefinitely preserving the same physical components.

Nevertheless, there remains a critical distinction between gradually replacing oneself and creating a separate, identical version. Even if a fantastical technology like mind uploading could precisely duplicate our consciousness, the resulting copy would inevitably diverge into its own distinct identity, living its own separate life. Cell replacement, by contrast, preserves and enhances the original self, with the profound advantage of keeping us firmly anchored in the physical universe rather than retreating into simulated realities.

Compared to the Gattaca future of embryo editing, enhanced cells are both more effective and less ethically fraught. Embryo selection faces a fundamental limitation: complex traits like intelligence or longevity depend on countless minor genetic factors, making genuine enhancement nearly impossible. Even if our editing tools and predictive models dramatically improve, any chosen genetic variant must remain harmless across every type of cell in the body, severely limiting our options. By contrast, intervening at the cellular level later in life dramatically expands our possibilities. Perhaps we could directly enhance neurons to form more connections or engineer heart cells to withstand stress, enabling meaningful improvements in intelligence and longevity.

The ethical considerations surrounding human enhancement are critically important and deserve deeper exploration than I’ve provided here. Still, I'll briefly address a few of the most pressing concerns. One reason that embryo editing feels troubling is because it attempts to shape a life before it even begins. Shifting enhancements from conception to adulthood allows individuals to thoughtfully decide if, when, and how to modify their own biology.

Another concern is uniformity: if everyone chooses the same genetic variants, we might become healthier but risk losing our individuality. Cell replacement could offer the best of both worlds. You'd still develop naturally, creating a unique biological foundation into which enhanced cells are later integrated, preserving much of the variation in external features like facial appearance. As with cosmetic surgery today, some people might undergo procedures to resemble their favorite celebrity, while others would use it to unlock entirely new forms of personal expression. But for internal functions—like your heart, liver, or immune system—wouldn’t everyone simply want the best version available? In this future, differences would remain, but biological diversity would increasingly reflect individual choice rather than a genetic lottery.

Most critically, unlike embryo editing, enhanced cell replacement deliberately leaves the germline untouched. Unlike specialized cells, germline cells must retain the potential to form every cell type to allow future generations to develop naturally, just as we have. These cells will carry on the essence of what makes us human: a genetic thread tying together past, present, and future.